HUMOUR THEORIES

Incongruity Theory

Incongruity Theory’s basic premise is that people find surprise and deviations from normal patterns humorous.

This includes deviations from cultural and societal norms, concepts, logic, laws (both natural and artificial), morals and stereotypes. In short, it is breaking from expectations.

Stephen Hoover suggests that incongruity can take the following forms: puns; physical comedy (e.g. Laurel and Hardy); social incongruity (e.g. Eddie Murphy in Trading Places); character incongruity (e.g. clergy not acting as we would expect in Father Ted); perspective incongruity (e.g. getting the wrong end of the stick in many Jeeves & Wooster stories); solution incongruity (e.g. suggesting a ridiculous action or solution to a problem, as found in this Bob Newhart sketch).

It should be noted that the object being perceived as incongruous does not actually need to be incongruous; it just needs to be perceived as incongruous by the recipient.

Benign Violation Theory

The Benign Violation Theory proposes that humour will only occur when the following three requirements are met:

- There is a threat of some sort (e.g. threat to a viewpoint or morals)

- Threat must be benign (i.e. so no real danger)

- The person sees 1 and 2 at the same time

This theory suggests that humour fails result because of the incorrect balance of threat (it is either too tame or too risqué) or it is not benign at all (so is perceived as aggressive).

An early version of The Benign Violation Theory was proposed by Tom Veatch around 1999, but has been reinvented and promoted heavily by Peter McGraw and Caleb Warren in the Humor Research Lab.

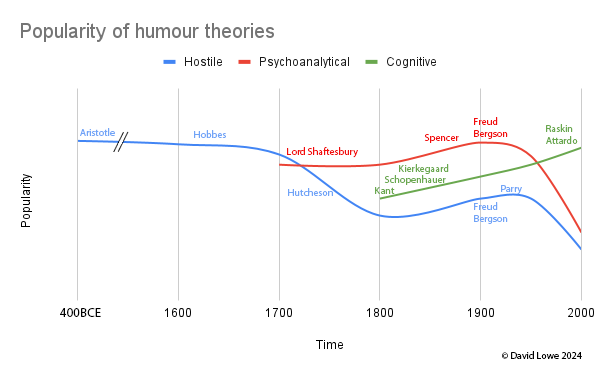

Superiority Theory

Early versions of Superiority Theory (going back to Plato and Aristotle) were contemptuous, implying that the focus (aka the butt) of the joke is considered inferior to the initiator making the joke.

Thomas Hobbes expanded Superiority Theory to make it more about a power struggle through humanity: everybody is in constant competition with each other, looking for signs that we are better than others – or at least that others are worse off than us – with laughter being an expression of triumph over someone else.

It’s a dated and unpleasantly aggressive theory, focusing on jokes about perceived physical disabilities, cultural differences, age, gender, sexual orientation, as well as misfortunes of others.

Some people criticised pre-Hobbesian Superiority Theory as not addressing self-deprecating humour; Hobbes’ version covers this by saying that self-deprecating humour is laughing at our previous selves.

Critics argue that it still fails to explain puns, laughter at oneself in the current moment (e.g. when we are in the process of doing something silly, rather than our former self) or self-deprecating humour. In response, Alexander Bain argued that laughter can be at non-human objects such as an idea or ideal (i.e. that we can find inanimate objects inferior).

Release Theory

Release Theory (also called ‘Relief Theory) believes that laughter is a way for the body to release pent-up, nervous energy by tricking the mind into letting it go.

Examples are sexual repression, closeted emotions, societal conventions and moral codes.

It will be of no surprise that Release Theory was promoted by the Freud, as well as the Earl of Shaftesbury and Herbert Spencer.

Mechanical Theory

The Mechanical Theory is an offshoot of the Superiority Theory: it laughs at the fixed thinking of people and society.

Play Theory

Great thinkers, including Aristotle and Saint Thomas Aquinas, have reminded us over the centuries that humour is needed in a busy life as playful relaxation.

St Thomas Aquinas (cited by Carroll) said that humour can act as a “remedy for the weariness of the active life, especially the active mental life.”